PREVIOUSLY: The girls discussed how they suffered so in their daily routines, and Jo called them a “jolly set.”

“Jo does use such slang words,” observed Amy, with a reproving look at the long, comparatively-healthy figure stretched on the rug. Jo immediately sat up, put her hands in her apron pockets, and began to whistle.

“Don’t, Jo; it’s so boyish.”

“That’s why I do it.”

“I detest rude, unlady-like girls.”

“I hate affected, niminy piminy chits.”

“Birds in their little nests agree,” sang Beth, the peace-maker, with such a funny face that both sharp voices softened to a laugh, and the “pecking” ended for that time. It always did. Whether by fashion or by force, Beth had the final word in companionability.

“Really, girls, you are both to be blamed,” said Meg, beginning to lecture in her elder sisterly fashion. The girls enjoyed her pretending at authority; for, indeed, sometimes older sisters do not stay older sisters. “You are old enough to leave off boyish tricks, and behave better, Josephine. It didn’t matter so much when you were a little girl; but now you are so tall, and turn up your hair, you should remember that you are a young lady.”

It’s bad enough to be a girl…when I like boy’s games, and work, and manners.”

“I ain’t! And if turning up my hair makes me one, I’ll wear it in two tails till I’m twenty,” cried Jo, pulling off her net, and shaking down a chestnut mane. “I hate to think I’ve got to grow up and be Miss March, and wear long gowns, and look as prim as a China-aster.1 It’s bad enough to be a girl, any-way, when I like boy’s games, and work, and manners. I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy, and it’s worse than ever now, for I’m dying to go and fight with papa, and I can only stay at home and knit like a poky old woman;” and Jo shook the blue army-sock till the needles rattled like castanets, and her ball bounded across the room. 2

“Poor Jo; it’s too bad! But it can’t be helped, so you must try to be contented with making your name boyish, and playing brother to us girls,” said Beth, stroking the rough head at her knee with a hand that all the dishwashing and dusting and sewing and pickling and dreaming and making and unmaking and making and unmaking and unmaking and making in the world could not make ungentle in its touch.

“As for you, Amy,” continued Meg, drawing a breath shorter than she would have liked. “You are altogether too particular and prim. Your airs are funny now, but you’ll grow up an affected little goose if you don’t take care. I like your nice manners, and refined ways of speaking, when you don’t try to be elegant; but your absurd words are as bad as Jo’s slang.”

1 It’s a flower!

2 I left this whole little speech untouched, partially because it’s famous and partially because it think it’s a fascinating picture into Alcott’s 1860s view on women’s lib (aka. the Point-Oh-Fifth Wave of feminism). I think LW is great way to do introduction to literary criticism, because it’s easier to put yourself in the “why was this revolutionary POV” at the time than say, The Great Gatsby. And when you can do THAT, you can pinpoint where Alcott pulled her punches, when she didn’t push herself enough. Meanwhile, there are entire lines of study devoted to LW’s ideas of gender, orientation, queer readings, all sorts of stuff! If you’re a reader and have any pieces like this you want to recommend, please send ‘em my way, I’d love to share.

We’re in the thick of it now, kids!

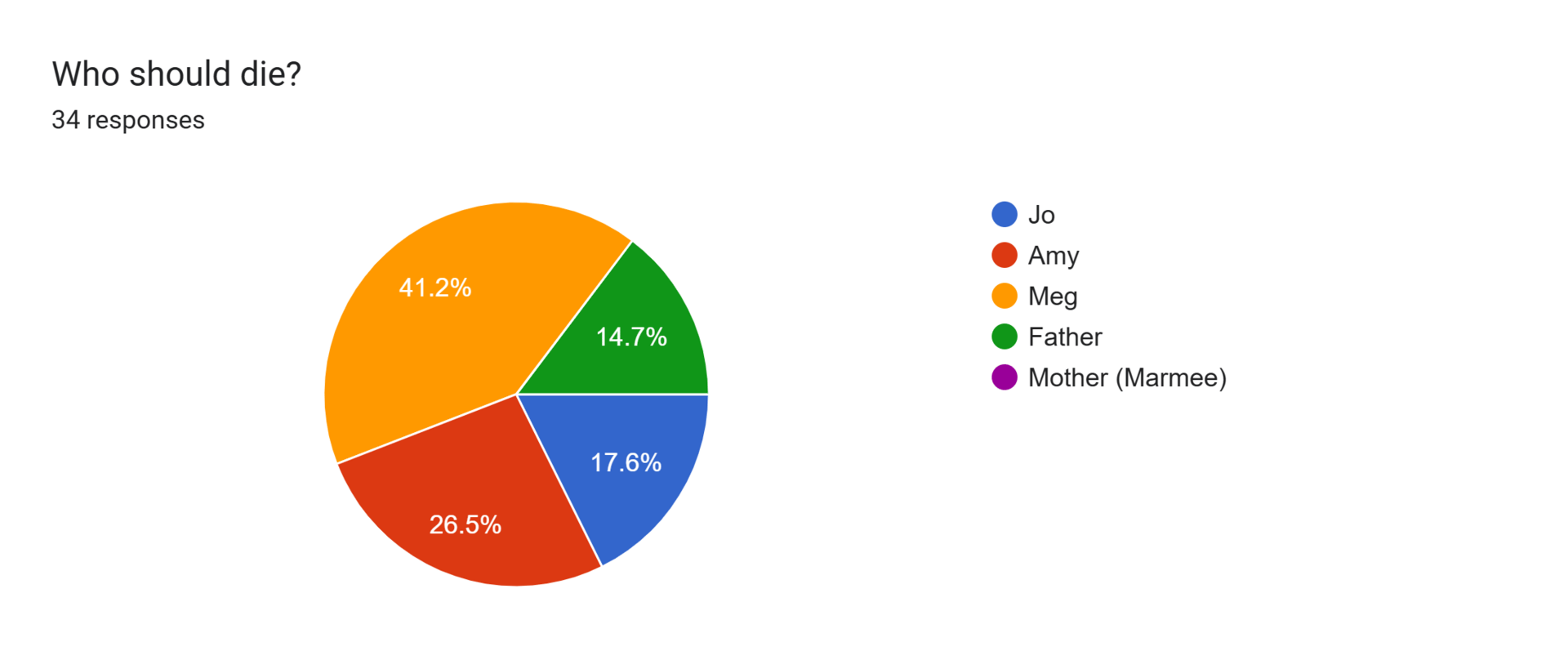

You’ll note that the Death Poll has moved to Google Forms I MEAN has always been in Google Forms, a wonderful free platform available for all your online needs. Ok love you see you Friday!

Your Weekly Death Poll Standings